Moment to Moment Mindfulness

Achan Sobin S. Namto

Contents

Foreword

Preface

Publisher's Foreword

Important Messages To The Reader

About The Method

Mind Development: Theory and Practice

What Is Insight Meditation?

The Benefits of Training

The Development of Vipassana Meditation

Investigating the Path

The Working-Ground of Mind Development

Differences Between Concentration and Insight Meditation

What is Mindfulness?

The Four Foundations of Mindfulness

Why Practice Step by Step Mindfulness?

Clear Comprehension

Factors Comprising Mind-and-Body

The Sense Bases

Distinguishing Mental Processes from Physical Processes

How to Focus on Mental and Physical Objects

Self-dedication to the Training

Preparations for Intensive Practice

Guidelines for Conduct

The Eight Precepts

On Entering Training

Commencing intensive Practice

Essential instruction for Beginners

Labeling Mental and Physical Objects

Mindfulness on Abdominal Movement or the Breath

Entering Practice: Making Resolution and Offering Salutation

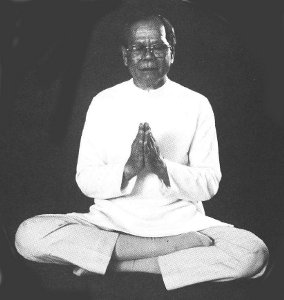

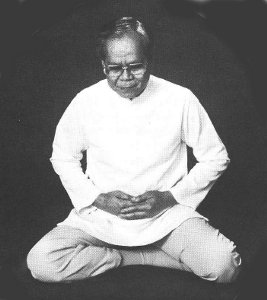

Introduction to the Sitting Posture

Changing from Sitting to Standing Posture

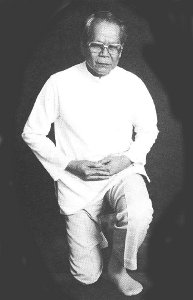

Introduction to the Standing Posture

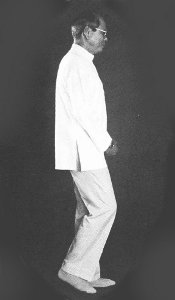

Introduction to the Walking Posture

Walking Schedule for Intensive Practice

Introduction to the Reclining Posture

Rhythmic Practice — Hand-By-Hand Mindfulness

Mindfulness at Mealtime

General Mindfulness

Concluding Intensive Practice — Transfer of Merit of Wholesome Deeds

Correcting Meditation Problems

How to Handle Physical Pain in Training

How to Correct Sleepiness and Dullness

How to Work with Severe Emotional Pain in Early Training

How to Handle Recurring Memories and Overactive Imagination

His Eminence the Somdej Phra Budthacharn

Acting Supreme Patriarch Of the Buddhist Sangha of Thailand

When the Venerable Maha Sobin S. Namto first became my close disciple in B.E. 2492 (1949), I was Abbot of Wat Maha Dhatu Monastery, Bangkok. I acted as Preceptor at his novice ordination, and later he became a monk at Wat Maha Dhatu, Bangkok.

Throughout the years, I have found him to be a forthright and amiable person. From the early days of his novitiate, he displayed a keen interest in practicing Vipassana (Insight) meditation. At that time, he was the very first novice to complete seven continuous, non-stop months of Insight meditation under the guidance of the late meditation master, Tho Most Venerable Chao Khun Bhavanapirama Thera. He continued to earnestly pursue his studies of Dharma (Buddhist teachings) and meditation. I appointed him as teacher and mentor to his students. He was highly respected by both the clergy and laity.

I am aware that the study and practice of Buddhism is the only way to gain its benefits. In B.E. 2495 (1953), 1 founded a Vipassana center at Wat Mat Dhatu. It is well known locally and internationally. Maha Sobin taught there for many years. I fervently wish that all monks, nuns, novices and laity dedicate themselves to faithfully serving and practicing the Dharma.

Maha Sobin has long agreed with my aspiration. Seeking to deepen his Dharma knowledge, I sent him for further studies with the Venerable U Visudha Sayadaw, Kabaae, Rangoon, Burma in B.E. 2500 (1957). Returning to Thailand, he continued as teacher of meditation and Abhidharma (Buddhist psychology) and Dharma. In 1960, I was pleased to honor the requests of the Lao Buddhist Sangha and the Head instructor for Vipassana Meditation, and the invitation of the Government of Laos to appoint Maha Sobin to teach meditation and Abhidharma at Wat Buddhavipassanaram Luangphrabang, Laos.

He resumed teaching in Southern Thailand. Phuket Province. where he established the Abhidharma Vidhyakorn Institute.

Later, the Most Venerable Chao Khun Dhammakosacharn, Chairperson of the "Wat Thai in America" Committee, selected him and four other monks to establish the first Thai temple in Los Angeles, Calfornia. Maha Sobin was appointed its first Abbot.

He is also the Founder-Abbot of a Vipassana temple in Denver, Colorado. In 1980 he decided to resign from the monkhood, but continues to dedicate himself entirely and untiringly to teaching Vipassana, Abhidharma and Buddhism to North Americans and the Southeast Asian community. He has established several meditation centers and has a number of Western disciples.

I was delighted to learn that he is the author of two books in English on insight meditation. I am confident these publications will be of great worth in transmitting the message of Vipassana meditation to the general public in the Western World. These offerings are the result of his many years of persevering effort on behalf of the Dharma.

May he and his Western disciples progress and find peace and contentment in the Dharma. May all beingss enter the stream of Buddha-Dharma forever.

His Eminence the Somdej Phra Budthacharn

Lord Abbot Wat Maha Dhatu, Bangkok

Director of Vipassana Meditation in Thailand.

Atitam nanvagameyya

yadatllampahlnsntam

pacrupannam ca yo dhammam

nappatikankhe anagatam

appattanoa anagatsm

tattha tattha Vipassati

"The past is gone: the future has not come. But whoever sees the Truth clearly in the present moment, and knows that which is unshakable, lives in a still, unmoving state of mind."

— The Buddha

Bhaddekaratta Sutta

For a long time, I have had the intention to write a book on insight (Vipassana) meditation based on the "Four Foundations of Mindfulness" of the Maha Satipatthana Sutta.

As a novice monk in Bangkok, monastic training centered on memorization of texts by rote. No manuals were available on Vipassana practice, but my teacher, The Most Venerable Chao Khun Bhavanabhirama Thera, did not teach us to parrot the material we learned by heart. He would reconstruct the building blocks of abstruse scriptural material in a systematic way until we had a thorough knowledge of our studies. No certificate was awarded for Vipassana study and very few novices joined these classes. In those days, the practice of insight meditation was not wide-spread, end I felt fortunate to be the student of so conscientious an instructor.

Almost 70 years ago, my teacher studied and practiced with extraordinarily gifted monks at the Burmese temple in Bangkok. Through the years, I had a number of instructors from whom I earned the principles of teaching Vipassana meditation, yet I retained the basic method of my first teacher, finding it to be a precise and highly eHective approach to training based on the early Commentary to the Maha Satipatthana Sutta.

When I arrived in California, I observed many Americans were introduced to meditation through the written word. Over 90% ot Buddhist books in North America explored the concentration practices of various traditions, but only a handful of publications are produced on Vipassana meditation, which is the earliest instruction given by the Buddha. As ffar as I know, no detailed book on the step by step approach to training exists on Insight practice in the West.

Therefore, I wrote the present book on theory and practical guidance for the novice and the more experienced meditator.

The publication of this book became a reality through the generous donations of practitioners and supporters. Inasmuch as they have offered the greatest of gifts— the teaching of the Dharma— the credit belongs to them for spreading the message of insight meditation.

May all Dharma Comrades share any merit gained through the publication of this book. May we all practice together to end delusion and suHering and realize the taste of Absolute Freedom, Nibbana.

I transfer any merit realized from the offering of this book to my parents, teachers, all friends who have supported me, and to all sentient beings. May we strive to eliminate suffering at all times.

— Achan Sobln S. Namto

Bangkok, Thailand

B.E. 2532/1989

Many individuals today, in unparalleled numbers, are burdened by a crisis of identity manifesting as stress-related disease or more severe mental symptoms. This personal crisis is mirrored in a world community continually plunging headlong into entanglements and turmoil in the political, social, religious and economic arenas.

Some thoughtful men and women have searched for and found an escape route from life's dilemmas, it not from misery, by the practice of mind development known as Insight (Vipassana) meditation. After realizing some benefits of the practice, meditators often feel bound to share this teaching with others, who, like themselves, are seeking for a solution to conflict. Perhaps, one day, Insight meditation may be an agenda item at meetings to settle global conflict!

The sharing of this teaching is growing in ever greater numbers. In a little more than two decades, interest in the practice of Insight meditation has captured the attention of mental health workers, educators and artists. It has had noticeable impact on the North American, European, and, to some degree, the world-wide spiritual community.

A discourse of the Buddha known as the "Four Foundations of Mindfulness" forms the foundation of the practice. Recorded by monks in Ceylon in the First Century, this teaching stands as a timeless reminder that the mind has changed little since ancient times. We remain afflicted, as did our forebears, with the endemic dis-ease of mental ills. Through the passage of two millennia, this "Proclamation of Emancipation" from mental bondage has not been lost. There is a WAY OUT of the human predicament for those who travel the course to completion.

Achan Sobin S. Nomto is one of a number of instructors now sharing the responsibility of teaching Insight meditation in North America.

Trained in the classical manner of a Buddhist monk, the then Venerable Phra Maha Sobin S. Namto was invited in 1972 by the Thai Sangha Council to establish the first Thai temple in the United States. Primarily a teacher of Vipassana and Abhidharma (Buddhist Psychology) for over 30 years, Achan Sobin made the teaching available to both Thais and Americans. As a result, Americans were soon requesting opportunities to enter intensive meditation practice under his direction. Some years later, he made the decision to widen his scope of activities by teaching as a lay instructor.

For over three decades, his major teaching duties in Thailand oentered around instructing thousands of teachers, monks and laity, many of whom intended to train others in the practice of Insight meditation and Abhidharma. As a teacher's teacher, Achan Sobin feels a keen obligation to preserve and transmit the pristine character of Vipassana meditation to the Occident, especially in these early days at establishing the roots of this extraordinary teaching of Deliverance.

Rather than diminish or dilute the "Gift of Truth" for popular consumption, Achan Sobin endeavors to maintain the integrity of the original intent of the training, that is, as a vehicle of Enlightenment. He has therefor retained a "no-frills" approach. Without compromising the principles of the training, he has made adaptations in only very minor features and has provided some options in certain matters for the convenience of Western meditators.

Achan Sobin's heartfelt wish is to leave a legacy of Western-born teachers to carry on the essential work of sharing this message of healing and liberation around the world.

May this offering encourage and guide your first steps on the Insight journey.

Important Messages To The Reader

- Persons under the care of a mental health worker who wish to enter training are strongly advised to discuss their intention with their psychotherapist, etc. If permission is given, consultation with the meditation teacher is necessary.

- Vipassana meditation is a path of Individualized instruction. While sharing certain routine activities with other meditators at a center, the training remains an individual training and not a group activity.

- The instruction offered in this book is a guideline for practice and cannot substitute for the essential personal contact between teacher and student. Prospective meditators are encouraged to find an instructor and enter training.

- As an introduction designed for novice meditators, only essential points of Vipassana theory have been included for meditators. Both Pali and Sanskrit terms have been minimally used when needed for clarity.

- In-depth meditation guidance, suitable for introductory, intermediary and advanced levels of training may be found in Achan Sobin's book entitled INSIGHT MEDITATION: Practical Steps to Ultimate Truth.

The technique of training detailed in these pages is an expanded method based on the original instruction of insight meditation developed by the late and renown meditation master, Mahasi Sayadaw, of Burma.

Achan Sobin has further elaborated the principle of step by step mlndfulness (a skillful training device) enabling the insight worker to gain increased benefits of the practice.

May devotees of insight meditation, in the years to come, further refine this most remarkable training as an offering to all seekers of truth.

Mind Development: Theory and Practice

Insight meditation (Vipassana) means inward seeing— seeing Reality as it is, not as we would like it to be. It brings a radical change in our personal world, a change in how we see ourselves and others. Insight is the tool which reveals the Awakened Mind of purity and clarity, allowing the perfection of the "Art of Living."

We are all familiar with the joys and disappointments which determine our day-to-day reality. Caught in the grip of neurotic emotions and attachments, we know something is not right— life hurts.

Yet, another Reality exists and there is another way to live. But what do we do with the massive forest of entangled emotions and thoughts collected through the years? Vipassana meditation uses all the contents of the mind as precious kindling. Insight meditation consumes the stress, frustration and pain which darkens our lives. This personal purification process, which may be practiced by persons of all faiths, restores the warmth of true humanity, cleanses mental impurities and develops complete mental health, if we are willing to put the training to the test, Insight meditation shows us who and what we are— and what we can become.

The technique is simple, systematic and direct. Training focuses on observing the mind in its natural state, with a non-attached, objective awareness (mindfulness) of what is actually present, moment to moment. Meditation is not our goal, but a tool for realization. No suppression of mental states occurs in the training. Unlike our normal attitudes and perceptions in daily life, which carry an ethical content, during the training period we observe only bare mental and physical phenomena.

A gentle, non-aggressive practice. step by step training strengthens consciousness of mind and body processes until intutitive knowledge, finely balanced and finely tuned, arises spontaneously for the meditator.

Practicing Insight meditation . . .

- Results in the experiential knowledge of Wisdom, and the abandonment of clinging to concepts, which are useful conventions, but which are not Ultimate Truth;

- Develops, in the deepest sense, a person of true spiritual culture;

- Develops loving-kindness and compassion, joy and peace of mind;

- Equips the meditator with self-knowledge which results in natural self-governing;

- Cultivates gratitude and gentleness;

- Promotes selflessness in aiding others, without ego-involvement;

- Gives relief from stress and anxiety in daily life;

- Promotes freedom from anger, worry, cravings, conceit, spiritual doubt, restlessness and mental turmoil;

- Develops the powers of concentration;

- Results in freedom from grief and sorrow;

- Banishes mental confusion by promoting clarity of mind and body states;

- Promotes the unity of humanity and respect for all sentient life.

The Development Of Vipassana Meditation

Insight meditation is based on the teachings of the historical Gautama Buddha, who lived in India (modern Nepal) in the sixth century, B.C.

The central teachings of Buddhism, which culminate in full spiritual Awakening, are based on the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path.

Traditionally, the Buddhist teachings comprise two complementary fields of activity (or duty) for monks, nuns and laity:

GANTHA DHURA — The study of the Buddhist Canon (the Tripitaka) consisting of the following texts:

ABHIDHARMA — Buddhist Psychology

SUTRAS — Discourses of the Buddha

VINAYA — Code of Discipline for monks and nuns

VIPASSANA DHURA — After studying the theory of Buddhist teachings, the Path is then developed by the practice of meditation which is divided into two areas: Samadhi> (concentration) and Vipassana (Insight).

In our present study we shall focus on Vipassana meditation, which leads to fruition of the Teachings, to the end of all mental sufferings, and to the realization of Enlightenment (Nirvana). This is the practice of Insight meditation, which rests on the base of Ethical Conduct (Sila) and Concentration.

Buddhism, as a non-proselytizing religion or Way of Life, encourages free inquiry and not blind belief; therefore, it is a path open to all for full investigation.

After deeply probing the nature of life, the Buddha came to the following conclusions and resolution:

The Four Noble Truths

- Life, by its imperfect nature, is unstable and basically unsatisfactory, due to the potentiality of stress, conflict and frustration (as opposed to stability and complete happiness).

- This distress is caused by a special kind of Thirst— the greed and attachment arising from delusion in not seeing the true nature of Reality.

- This condition of conflict and pain can cease with release from greed and neurotic clinging.

- Freedom from this stress-frustration-pain cycle is realized by investigating, testing and practicing THE NOBLE EIGHTFOLD PATH:

The Noble Eightfold Path

Consists of:

RIGHT (complete or balanced) UNDERSTANDING

RIGHT incomplete or balanced) INTENTION

RIGHT (complete or balanosd) SPEECH

RIGHT (complete or balanced) ACTION

RIGHT (complete or balanced) LIVELIHOOD

RlGHT (complete or balanced) EFFORT

RIGHT (complete or balanced) MINDFULNESS

RIGHT (complete or balanced) CONCENTRATION

The Working-Ground of Mind Development

The normal mind is always thinking, restless, disquieted and rarely still. Often overwhelmed and smothered by mental hindrances or taints, we find ourselves designing our own suffering day in and day out, from birth to death. When the mind is not grounded in a skillful wholesome mental state, it ranges far and wide, untamed, uncontrolled, weak and inefficient. Fortunately, it possesses great potential to be tamed, to become pliable and fit for work. The potential of the mind is enormous.

Each of us has a mental "work station"— a base or ground for mind development. The Pali term kammatthana may be divided into kamma (action) and thana (work). It is the place of practice where one works on the mind. It is the working-ground of the mind in which Insight develops penetration of the Truth. It plays an indispensable role in Insight meditation.

There are two kinds of working~rounds for mental cultivation, namely:

Samadhi Bhavana, or Concentration meditation leading to Tranquility and blissful states. The defilements or passions are temporarily subdued by the power of concentration

and

Vipassana Bhavana, or Insight meditation. which leads to penetrating Knowledge. This, in turn, unfolds the Wisdom of Enlightenment and the destruction of Ignorance— of all mental cravings and afflictions.

Differences Between Concentration and Insight Meditation

Concentratlon (Samadhi) meditation methods existed many centuries before the birth of the Buddha. These methods reflect one stream of meditative practice consisting of 40 traditional subjects, as listed in Classical Buddhism. These methods are divided into six categories, based on the temperament of the meditator.

Samadhi practice focuses on conventional reality, with attention directed to a single object, such as an image (visualization) or a sound (mantra), or the breath. Its practice leads the devotee to advanced states of tranquility, called tranquility adsorptions. The every day hindrances of sensuality, ill will, lassitude, worry and skeptical doubt are temporarily suppressed. Consciousness gradually ascends to the blissful states of the realms of form and formlessness, retaining only the barest trace of consciousness. The meditator then experiences ""voidness" or "emptiness" of mind. These states, especially the latter adsorptions, are rare and difficult to accomplish.

The external requirements for that form of practice include quiet, solitude, good companionship, etc. Such Samadhi attainments result in the cultivation of many special abilities, even psychic powers. It is the path of the Bodhisattva, bestowing strong mental powers to aid others. The feeling, upon reaching the limits of samadhi, is that of permanent happiness of the sex. However, with that form of meditation, delusion is still present.

Vipassana or Inslght meditation, as distinct from samadhi, is the vehicle leading to full Liberation. It is ultimate knowledge of Reality, eliminating ignorance, which is the causative factor of suffering from mental pollutants. Unlike the practice of samadhi, which focuses on external objects, Insight training examines that which is closest to us— our own mind-and-body. These constitute the only objects for the practice of Insight meditation. It was the genius of the Buddha who re-discovered this Path of Insight for the realization of Ultimate Truth.

The dawning of deliverance signals, and is accompanied by, the cessation of all mental defilements. The Four Noble Truths are penetrated and the Noble Eightfold Path is traversed to completion. The knowledge which dawns when this state of realization occurs is that of the Truths of Impermanence, of Suffering and of Non-Self. Nirvana is Ultimate Release from suffering, from the recurring cycles of Birth-and-Death.

Mindfulness is the direct experience of touching only the present moment of our lives. When training in the practice, the meditator can directly experience the constant shifts of the phenomenal world and not be led astray by deluded thinking. This experience is entirely different from theorizing or conceptualizing information about reality. We will understand that the present moment is the only time for living.

Mindfulness is focused attention placed on any mental object (thinking, anger, calm, etc.) or any physical object (body postures, movement, breathing, etc.)

Physical (form) objects are simply materiality and, of course, do not possess consciousness. Form is an object of the mind; it is consciousness which knows form. During Insight training, the meditator needs to know form in the present moment only. Among the many types of mental and physical forms, there are eye-, nose-, touching and thinking forms (ideation is considered a sense-form). Of the 28 different types of form recognized by Buddhist psychology (Abhidharma), the above forms are mainly used in Vipassana meditation training.

Mindfulness, a mental factor, is a tool used in training and is subject to flux. It rises and falls, and varies in intensity. It cannot be artificially manufactured. The Insight worker needs to have the mind constantly moving on to the next object in consciousness, that is, focusing on the present object and then "forgetting" or releasing it. Mindfulness should not be grasped. TOUCH-AND-GO is the KEY to mindfulness practice.

Whatever physical or mental object appears in consciousness is the present object on which mindfulness focuses attention; therefore, no need arises to "search" for objects. Essentially, Vipassana allows us to know (be mindful of) any object "touching" the mind on a momentary basis. This "knowing" can itself moderate any extremes of mental agitation or excesses of any type.

The Four Foundations of Mindfulness

The "Four Foundations of Mindfulness" of the Maha Satipatthana Sutta, as taught in early Buddhism, serves as the primary base of insight meditation practice. They are as follows:

- Mindfulness of Bodily Objects (breath, movement or postures)

- Mindfulness of Feelings (pleasant, unpleasant or neutral sensations)

- Mindfulness of States of Consciousness (mind with or without greed, hatred or delusion)

- Mindfulness of Mental Contents (joy, apathy, worry, calm, doubt, restlessness, etc.)

Or, simply stated, mindfulness of BODY, FEELINGS, MIND and MENTAL OBJECTS.

The practice of the Four Foundations is the same practice as following the Eightfold Path, as both constitute practice of the Middle Way.

The Four Foundations are objects for the focusing of mindfulness in the present moment. By doing the work of the Four Foundations, or by following the Eightfold Path, the meditator destroys aversion for and attraction to objects, thus achieving balance of mental factors.

Why Practice Step By Step Mindfulness?

While impossible to fully observe the incredible flux of mind, step by step mindfulness training is designed to go against the streams of our habitual action-reaction response and normal routine.

Step by step observation results in the de-acceleration of the mental flux, training the mind to remain in the present moment for close investigation. Reduction in the speed of physical movement Slows the minds sufficiently to permit scrutiny of the highlights of activity. It is also the "action of mind" which works as skillful means, enabling Wisdom to see the Truths of Impermanence, Dissatisfaction and Non-Self. The technique is a training device, and not an end in itself.

Mind and body states arise and cease with the FOUR MAJOR POSTURES, with MOVEMENTS OF THE BODY, and with the SIX SENSE BASES.

This technique permits the observation of the rising-and-falling of EACH change of posture, EACH physical movement, and EACH shift in the mental process. Therefore, the principle of step by step mindfulness training fulfills the criteria of practice in the "Four Foundations of Mindfulness" discourse given by the Buddha, and its commentarial literature.

This technique permits easy focusing on objects as they arise in consciousness, one by one on a momentary, non-stop basis. This last factor is a fundamental KEY to practice.

As mindfulness matures, physical movement reestablishes itself in a more natural pattern.

The applied form of mindfulness in daily life is called Clear Comprehension, which we carry with us throughout our ordinary life. Clear Comprehension is WISDOM IN ACTION and is a vast field for cultivation.

Clear Comprehension and mindfulness work in tandem by penetrating the object or action with regard to its purpose and nature. It shows us how to proceed skillfully in any situation, free from deluded mental states. It differs in application with each individual, just as the quality, intensity and usefulnes of light depends upon its source.

Clear Comprehension conveys the duty of deeply probing the Truths of Impermanence, Unsatisfactoriness and Insubstantiality (Non-Self). As an active factor, clear comprehension permits us to mold our karma (volitional activity). To a great extent, we can learn to respond to circumstances in a skillful way.

Functioning as the Wisdom Faculty, clear comprehension regards and fully comprehends the object contacted by mindfulness and prevents the birth of delusion. Since no ignorance is associated with the object, defilements cannot arise. By investigating the phenomenal world in this manner, without the overlay of emotional states, conceptualizations or bias, the individual achieves non-attachment to the "passing show" yet still maintains efficient functioning in daily life.

Clear Comprehension is effort which is correct and timely. It is a state informed by mindfulness at all times, on a momentary basis.

Factors Comprising Mind-And-Body

According to Buddhist Psychology, the human mind and body can be analyzed in terms of factors called the FIVE GROUPS OF CLINGING. These groups comprise the interlinked elements which are regarded as a temporary personality.

The Five Groups Of Clinging

- Form (physicality)

- Sensation (pleasant, unpleasant or neutral physical or mental feeling)

- Perception Memory, world of ideas)

- Mental Formations (faculty of mental activity

- Consciousness Awareness of various objects)

The above elements can be reduced to Four Mental Factors and one Physical Factor or, simply

The Mind-And-Body States

These mind-and body states arise and cease, arise and cease, arise and cease, with the four major postures of the body, the movement of the body, and the sense bases.

In the ordinary unenlightened being, mind-and-body conditions create mental afflictions or defilements. They are the infrastructure of the First and Second Noble Truths. However, mind-and-body are also the path to Enlightenment, for it is mindfulness which is walking on the Path. Insight meditation is the practice pursued until the meditator can experience the state of insight which understands physical and mental phenomena as rising and falling away. 7his realization of Insight-Knowledge is based on the practice of Insight meditation.

No overriding "Self" can be found to control the appearance and disappearance of mind-and-body states. Penetrating the nature of physicality and mentality leads to the Truths of impermanence, Suffering and Non-Self.

Mentality-and-physicality states arise and cease at the six INTERNAL and the six EXTERNAL sense-bases (including mind or consciousness), namely:

Internal Sense Base

Eyes

Ears

Nose

Tongue

Body Mind-base

External Sense Base

Visible Object

Sound Object

Odor Object

Taste Object

Body-lmpression Object

Mind-Object

Therefore, whenever

eyes see a form - mind-and-body conditions arise and perish instantly;

ears hear a sound - mind-and-body conditions arise and perish instantly;

nose smells an odor - mind-and-body conditions arise and perish instantly;

tongue tastes a taste - mind-and-body conditions arise and perish instantly;

and when

body contacts something cold, hot, soft or hard—

mind-and-body conditions arise and perish instantly;

and when

mind creates or seizes an idea—

mind-and-body conditions arise and perish instantly.

While the groups mentioned above serve as the main objects for the majority of insight workers, the Vipassana Bhuml (or "Grounds for Establishing Insight") outlines a comprehensive list of all objects used in training (though not intended for use by new meditators). Six categories are mentioned which total 73 objects for practice.

The birth of greed, hatred and delusion arise and cease at the six internal and External sense bases. Lack of mindfulness with regard to the reality behind sense formations causes delusion and mental taints to arise in either subtle or gross form. Their appearance clouds the mind, which is originally luminous and pure.

Distinguishing Mental Processes From Physical Processes

Before commencing the practice of insight meditation, it is essential the aspiring meditator learn to distinguish mental and physical processes.

It is impossible to practice vipassana meditation correctly without this fundamental information.

In seeing a form:

THE COLOR AND THE EYES ARE FORM;

CONSCIOUSNESS OF SEEING IS MIND-KNOWN.

In hearing a sound:

THE SOUND AND THE EARS ARE FORM;

CONSCIOUSNESS OF HEARING IS MIND-KNOWN.

In smelling an odor:

THE ODOR AND THE NOSE ARE FORM;

CONSCIOUSNESS OF SMELLING IS MIND-KNOWN.

In tasting:

THE TASTE AND THE TONGUE ARE FORM,

CONSCIOUSNESS OF TASTING IS MIND-KNOWN.

In touching:

THE OBJECT CONTACTED (cold, hot, soft or hard) AND THE BODY ARE FORM;

CONSCIOUSNESS OF CONTACT IS MIND-KNOWN.

When sitting:

SITTING IS FORM;

CONSCIOUSNESS OF SITTING IS MIND-KNOWN.

When standing:

STANDING IS FORM;

CONSCIOUSNESS OF STANDING IS MIND-KNOWN.

When walking:

MOVEMENT IS FORM;

CONSCIOUSNESS OF MOVEMENT IS MIND-KNOWN.

When reclining:

RECLINING IS FORM;

CONSCIOUSNESS OF RECLINING IS MIND-KNOWN.

When mindful of abdominal movement or when focusing on the breath:

RISING AND FALLING OF THE ABDOMEN OR BREATH IS FORM;

ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF THE MOVEMENT IS MIND-KNOWN.

The whole body is form and mind perceives materiality. Form (materiality) cannot know anything by itself. Form is only the object of the mind.

Only mind-and-matter exist In the world!

Knowing is the observing consciousness. There is only one meaning to Knowing in insight meditation, that is, being aware of mental and physical objects rising-and-falling in consciousness, on a momentary basis (object by object).

We designate objects conventionally by giving them names or labels; ultimately, however, there is no "being," no "I," no "self," no "he," "she," and so forth.

How To Focus On Mental And Physical Objects

It is essential that a new meditator understand how to focus mindfulness correctly and completely on a mental or physical object.

The Insight worker has to know (be mindful of) "feeling" with the object. Feeling, in this context, means that attention is focused on the object.

- on a momentary basis

- in the present time, and

- in its rising-and-falling phases.

All three factors must be present to constitute a complete and correct object of mindfulness.

Feeling, as an emotional state, or feeling as a pleasant, unpleasant or neutral mental and physical sensation, is not what is referred to here.

You can experiment yourself by lifting your arm in a normal motion, as performed in everyday life. This type of general mindfulness or awareness is somewhat vague and dispersed. Now lift your arm quite slowly, giving focused attention to the intention to move, the initial lifting, intermediate lifting and stopping of the movement. Now lower the arm in the same manner, noting the falling stage and stopping of movement.

Are you aware of the great difference between each of these actions?

Self-Dedication To The Training

An important area of Insight practice usually overlooked in the West is the aspirant's need to voluntarily dedicate oneself to the training.

While it is certainly possible to progress in Insight practice without such formal dedication, if one is sincere and earnest, knows the correct path, and has the right attitude, still, throughout the centuries-old practice of Insight meditation, Buddhist and non-8uddhist meditators have reaped many benefits from a firm self-resolution, formally made. In Southeast Asia, entering Vipassana training is considered a pivotal experience in one's life. This tradition has also contributed to safeguarding the training from commercialism or other interests.

The Following section reflects the attitude of the aspirant who desires to observe this custom. In a sense, it is a "by-law" of training and is usually not repeated, unless a special request is made if desired, non-Buddhists may lake all or any part of this brief observance.

Having dedicated oneself to the practice, the meditator, when confronting the inevitable challenges of training, can face them with composure, recalling the invincible courage of the Buddha (and other great spiritual figures) who faced these or similar trials with utter fearlessness.

The relationship established between teacher and meditator for the training period serves as a mutual commitment. The meditator gives permission to the teacher to guide and correct the training and knows that he or she is not practicing in isolation. The meditation teacher is the Good Friend in Dharma (the Teachings) and pledges to assist the meditator in every way, guiding and supporting the training. Communication links are established and practice begins on a sound basis of mutual confidence.

Preparations For Intensive Practice

- For the period of intensive training, meditators are requested to arrange all external activities (family, business affairs, etc.) prior to entering practice, providing, of course, for emergencies. This is in order to allow an uninterrupted period of practice.

- Please forego reading, writing, practicing other forms of meditation or religious exercises (mantras, visualization, prayer, etc.), and other activities. Practice mindfulness exercises exclusively.

- Except at interview time, intensive retreats are conducted in total silence.

- Beginners are individually interviewed daily, and as needed.

- Whenever possible, the staff is instructed to assist the meditator. It is preferable that the Insight worker perform no housekeeping chores, etc. during this training period.

- The practice of tasting is not permitted.

- Please report any illness or accident immediately to the assistant or teacher.

- Telephoning or leaving the premises is not allowed without specific permission.

- Wear plain, loose and easily laundered clothing.

- Eat enough food and sleep the minimum number of hours required for good health.

For the period of commitment to intensive residential training, all meditators are requested to voluntarily accept the Eight Precepts. The practice of observing the precepts reveals many aspects of the meditator's mind; designed to simplify the training period and moderate the daily life of the meditator, observance of the precepts enables attention to focus solely on the practice.

Most Vipassana meditation centers offer the Five or Eight Precepts. Another lesser-known set of Precepts exists called the "Eight Paths of Right Living" (Ajiva Attha Sila Magga) or the "Middle Way Precepts." They are suitable for daily living as well as for intensive practice. Both sets of precepts are listed on the following page.

These codes of conduct are complementary in nature. One set of guidelines is not superior or inferior to the other. The first guideline is strict with regard to worldly convention; the second code is more practical and reflects a higher standard of ethical behavior. The rule for maintaining silence during intensive training was developed from the Middle Way Precepts.

Depending on the meditator's inclination, health, age, as well as facilities offered at a meditation center, the practitioner has the option of choosing to abide by either set of guidelines.

The meditator may voluntarily choose to take either set of precepts, agreeing to abstain from the following:

| Eight (Standard) Precepts | Eight Paths Of Right Living |

|---|---|

| Intentionally taking life | Intentionally taking life |

| Stealing | Stealing |

| All sexual conduct | All sexual conduct, taking intoxicating drugs and drinks |

| False and useless speech | Useless speech |

| Taking intoxicating drugs or drinks | Lying speech |

| Eating solid food after mid-days* | Harsh speech |

| Seeing shows and using cosmetics | Gossiping speech |

| Using very soft beds | Bearing tales |

*Coffee, tea, chocolate, juices, soft drinks, clear soup, yogurt and cheese are permitted, Meditators are advised to moderate intake of food (to avoid sleepiness, etc.).

- Endeavor to be mindful of EACH and EVERY movement on a momentary basis. The meditator should try to sit, walk and perform any action mindfully without wishing to discontinue or interrupt the training, using skillful means to see what is happening in each moment.

- Make a positive resolution that you will not be discouraged as long as the end of suffering has not been accomplished. Work with balanced effort— not too loose and not too tight. Stay in the Middle Path, and mindfulness training will not be a burden. When you lose mindfulness, just begin again, and again.

- Mental taints and hindrances need to be challenged. "Welcome" them as teachers and regard them with mindfulness. They rise-and-fall continuously in consciousness.

- During the early stages of training, mindfulness alternates with delusion. It is similar to quickly switching a light on and off in a dark room. If a moment of clear attention follows a moment of delusion when mindfulness is dropped, a wholesome mind has immediately arisen.

- A new meditator has to "babysit" mindfulness. Mindfulness has to learn how to sit, stand, walk, eat, etc., and it cannot keep up with these actions all at once. When it "grows up" and becomes independent and can take care of itself, it can cooperate with other factors in training. The "babysitter" in mindfulness is the object in the present moment.

- Problems in practice need to be discussed with the teacher, whose commitment is to help and work with you. Don't let meditation problems linger around without resolution. It delays training in Insight practice.

- Don't practice with desire to achieve any state of Realization, Insght-Knowledge rises by itself.

- During training, please avoid:

- making jobs for yourself, such as non-essential cleaning, or other work, to escape boredom;

- indulging in excessive sleep, with consequent loss of effort. Sleep only 4-6 hours each night;

- seeking company;

- loss of restraint of the senses;

- immoderation in eating;

- failing to acknowledge mental activity when the mind seizes on or loses hold of an idea.

- It is a principle of practice that attention is focused solely on your own training.

- WHEN YOU CLEARLY UNDERSTAND THE PRINCIPLES OF TRAINING, THEN "PRACTICE" FUNCTIONS BY ITSELF. YOU WILL SIMPLY CARRY OUT EVERY ACTION AS A NATURAL DUTY OF THE MIND.

A meditator voluntarily accepts the Eight Precepts for the duration of formal training.

A Buddhist may pay respect to the Triple Gem of the Buddha (Teacher), Dharma (universal Law or Truth), and Sangha (Order of Enlightened Disciples). Non-Buddhists may make a suitable acknowledgment to faithfully practice and to respect the training.

Please repeat, in the ancient Pali language, after the meditation teacher:

IMAHAM BHAGAVA ATTABHAVAM TUMHAKAM PARICCAJAMI.

"Teacher, may I pay you respect for the purpose of practicing Insight meditation from this moment!""

NIBBANASSA ME BHANTE SACCHI KARANATTHAYA KAMMATTHANAM DEHI.

"Teacher, will you give me instruction for insight meditation so that I may comprehend the Path, the Fruition and Enlightenment later?"

Extend your friendship to all beings.

Please repeat after the Teacher:

"May I and all beings be happy, free from suffering, free from longing for revenge, free from troubles, difficulties and dangers.

May all beings be protected from misfortune and loss.

May all beings have the strength of mind to conquer their own suffering.

All beings have their karma. They have karma as their origin, as heredity, and as refuge. Whatever karmic activity one performs, by body, speech or mind, be it wholesome or unwholesome, returns to one."

Remind oneself of the brevity of life.

Please recite:

"Our lives are transient and death is certain. That being so, we are fortunate to have entered upon the practice of Insight meditation on this occasion, as now we have not been born in vain and have not missed the opportunity to practice the Dharma."

Recall that this practice of Insight meditation is that of all the Buddhas of the past and their enlightened disciples.

Please recite:

"The 'Four Foundations of Mindlulness,' as taught by the historical Shakyamuni Buddha, is the Path comprehended by the Wise. On my own initiative and to the best of my ability, I will follow the Path in sincerity to realize its highest fruition, Enlightenment. I will practice from this moment onwards.

In memory of the Buddha, I offer this practice of Dharma worthy of Dharma."

Essential Instruction For Beginners

In the exercises described below, focused attention (mindfulness) is placed on the sitting, standing, walking movement, reclining, abdominal movement or mindfulness of the breath, eating, etc. No activity is outside the scope of training.

STEP BY STEP MINDFULNESS (object by objects, as demonstrated in these pages, INCREASES the opportunities for mindfulness to focus on the rising-and-falling aspects of objects, on a momentary basis in a CONTINUOUS sequence.

Instructions given to new meditators emphasize focusing mindfulness mainly on the movements of the abdomen and walking. This Initially narrow focus facilitates the learning of the method and develops momentary concentration in a relatively short time. Later, the meditation teacher will vary instructions for balancing concentration and mindfulness and other factors in training.

The exercises are designed for retreat oonditions, but may be modified for non-intensive or daily practice.

Most meditators tend to break the momentum of continuous mindfulness when changing postures. Please follow through with the principle of cultivating STEP BY STEP (object by object) mindfulness. When "breaks" appear In the practice, just begin again and again.

THIS IS THE KEY TO CORRECT AND COMPLETE PRACTICE.

Labeling Mental And Physical Objects

Newcomers to mindfulness training may facilitate knowing objects appearing in consciousness by mentally repeating "seeing," "hearing," "thinking," etc., or "heel up," "lifting," and so forth.

Labeling phenomenal objects serves certain useful purposes, lessening excessive and obsessive mental or physical activity. Labeling also helps to root out the mistaken but embedded notion that a "self" performs or is responsible for the rising-and-falling away of mental-and-material states.

As practice matures and mindfulness directly knows objects, these labels, used in the beginning as a temporary aid, will automatically fade away as focusing becomes more natural.

Mindfulness On Abdominal Movement Or The Breath

The following instructions on mindfulness on abdominal movement may be adapted for meditators who have already established a practice of focusing attention on the breath in the nasal area. Generally, focusing on the breath produces a degree of tranquility which is too intense for insight work. Insight meditators are instructed not to follow the breath inside the body. Focus mindfulness only on knowing the in-and-out breaths as they occur, on a momentary basis. Take a comfortable sitting posture on a floor cushion, low bench or chair.

- New meditators are asked to focus mindfulness on abdominal movement in a relaxed and alert manner.

- If movement is vague, place your hand on the abdomen until the rising-and-falling stages are clear.

- Do not try to consciously control Ihe movement.

- When breathing in, the abdomen rises; when breathing out, the abdomen falls. Place attention on a spot about two inches above the navel. Be mindful of the appearing-and-disappearing aspect of each phase as it occurs, on a momentary basis.

- As a beginner, you may label the movement by mentally noting "rise" and "fall," or "in" or "out."

- If movement becomes long, short, shallow or deep, simply name the ocurrence and return to knowing "rise" and "fall"— your "anchor" object.

- If movement seems to disappear, acknowledge "disappearing." When movement returns, note it accordingly.

- If the mind becomes calm, note "calm mind."

- If the mind wishes to think, permit it to do so. Thinking, as with any other object, rises and falls. Acknowledge "thinking," "planning," "anger," "joy," etc., and return to observing the "anchor" object.

- If attention is averted to a strong external stimulus, such as hearing, note "hearing" and return to the "anchor" object.

- The beginner's mind will wander frequently. As soon as you are aware of attention straying, note "wandering mind" (or another word), and return to the "anchor" object. Observe all mental states coming into existence, peaking and fading away.

- As much as possible, the beginner should try to be aware of abdominal movement or mindfulness of the breath.

Sit for 30, 45 or 60 minutes. Do not sit less than the minimum or more than the maximum time. A period of mindfulness on abdominal movement or the breath is alternated with mindfulness on other postures. As mindfulness increases, the experienced meditation teacher will give further instructions.

Mindfulness: Step By Step Illustrated Instruction

Practice: Making Resolution and Offering Salutation

RIGHT HAND

Mindfully:

- Place hands flat on knees.

- Turn right hand on its edge; stop.

- Bring forearm straight up (not too high or low); stop.

- Bring hand horizontally to mid-chest; stop.

LEFT HAND

Mindfully:

- Repeat steps 2-3 with left hand.

- Bring hand horizontally to mid-chest, but stop before touching right hand.

- Touch hands.

- Lower head slightly.

- Make resolution, pay respect.

TO RETURN EACH HAND TO KNEES

Mindfully:

- Raise head.

- Move right hand horizontally out (sideways); stop.

- Move right hand straight down towards knee; stop before touching.

- Touch knee (hand is still on edge); stop.

- Turn hand over (palm down) to rest on knee.

- Repeat steps 2-5 with left hand.

Introduction To The Sitting Posture

Assume a comfortable position, either on a thick floor cushion, bench or in a chair (preferably with no back rest). A hardwood slanted meditation bench is 20 inches long, 6 inches wide, and 6 inches high. Legs are tucked underneath the bench. A meditation cushion is approximately 10 inches high and 14 inches in diameter. A hard foam rectangle is 18 inches long, 12-1/2 inches wide and 6 inches high.

Persons with physical problems may adjust the sitting arrangement as necessary.

If seated on the floor, adjust to a comfortable cross-legged position which can be held relatively stable for 30, 45 or 60 minutes. (If too uncomfortable, you will not acquire any concentration.)

Keep the room temperature slightly on the cooler side. Do not try to shut out ordinary street noises, but beginners will find a relatively quiet place useful in the early stages of training.

Wear loose clothing. Keep the back straight and relaxed. Hold your head gently upright. Relax the muscles in your scalp, face, neck and shoulders. Eyes may remain closed or half-closed.

Focus on the sitting posture for 2-3 minutes by placing attention momentarily on the hands resting in the lap. Do not focus on the entire form sitting. Acknowledge "sitting."

When focusing on sitting, the beginner may target mindfulness by focusing momentarily on the hands in the lap. Do not focus on any other place. (Focusing on the whole body sitting is difficult for beginners.)

Mindfully focus on sitting 2-3 minutes before meditating on abdominal movement or mindfulness of the breath.

Changing From Sitting To Standing Posture

If sitting on a floor cushion (adapt for other sitting styles), note intention to move.

Move SLOWLY, focusing attention on one action at a time as you follow through with step by step mindfulness (object by object). Maintain the continuity of the technique.

Be mindful of tilting the torso, the shifting of the cushion (if using two hands, focus on one hand), the shift of weight, the moving of each leg, the placement of the toes of each foot, the stretching of the body, the raising of each knee, and the raising of the body to its full extension. Use one or two hands, if necessary, for balance.

Note intention to move and mindfully bend body. Take your time.

Mindfully note body rising.

Mindfully raise to one knee at a time.

Introduction To The Standing Posture

When moving to a standing posturer be mindful of "intention to stand." Acknowledge "standing."

Stand mindfully with arms hanging down at sides. Relax head, neck and shoulders. Eyes may be closed or directed about three feet ahead. If necessary to shift weight, note the shifting movement.

If mind wanders, note the mental state and return to acknowledging "standing."

Persons with physical problems may reduce standing time or omit this posture.

What are you doing? Standing? What is standing? Body (form) is standing. What knows standing? Mind or consciousness knows standing.

Beginners may focus mindfulness of standing at the soles of the feet, at the abdomen, or at another clear point.

Stand 10-15 minutes, or 30-60 seconds and go on the walking movement.

Introduction To The Walking Posture

For walking meditation, an area permitting about 20 paces is ideal, although smaller spaces can be used. Walking is best done in stocking or bare feet, on a bare or carpeted surface, preferably with a neutral and plain background.

In order to minimize distractions for the beginner, walking is done indoors.

Acknowledge the "standing" posture and "intention to walk." Relax the head, eyes, neck and shoulders. Direct eyes about three feet ahead. Place hands in front, crossed at wrists. Walk in a straight line, gently and slowly. Do not pay attention to the breath or muscle movement in the leg or foot. If impatience, boredom, etc. rise, note the mental state, but keep to the specified time you have determined for walking (30, 45, or 60 minutes). Persons with physical problems may adjust the practice as necessary.

If you wish to stop walking because of tiredness, mindfully stand for a few minutes, and then continue walking.

If you leave the meditation room, do not break the continuity of mindfulness. Mindfully walk to the door, note touching the door knob, coldness, hardness, turning, pulling, etc. Focus step by step mindfulness walking down the hall.

Walking Schedule For Intensive Practice

FIRST DAY:

Right foot goes

Left foot goes

SECOND DAY:

Lifting and placing

THIRD DAY:

Lifting, moving and placing

FOURTH DAY:

Heel up, lifting, moving, placing

FIFTH DAY:

Heel up, lifting, moving, lowering, placing

SIXTH DAY:

Heel up, lifting, moving, lowering, placing, pressing

Non-Intensive Practice

During non-intensive practice, meditators may experiment by focusing mindfulness on the first, second or third stages of walking, that is, whichever stage is clear.

What are you doing? Walking (moving). What is walking? Body (form) is walking. What knows walking? Mind knows walking.

Time for walking mindfulness is usually balanced with sitting meditation on abdominal breathing or mindfulness of the breath.

Third part: Mindfully note "moving."

If the mind is inattentive, note "wandering mind," etc. and return to the movement. It is not necessary to stop walking. If you lift your eyes, note "seeing."

Mindfully lower foot to the floor.

Sixth part: Mindfully note "pressing."

Continue walking mindfulness until you reach the end of the walking path. Note "intention to stop." Place feet together. Note "stopping," "standing." Focus on standing about 30 seconds.

As you approach the end of the walking path, try to note the "intention to stop," and then "stopping." Note placing the feet together and standing.

You may rest mindfully for about 30-60 seconds before turning in the opposite direction. Focus on "standing."

Note "intention to turn." Pivot slowly on one foot, in either direction, making little turns, until you face the opposite direction.

Refocus your eyes, and note "seeing," "standing" (for about 30 seconds) and note intention to walk. Walk, mindfully, in the opposite direction.

Introduction To The Reclining Posture

Unless weak or ill, newcomers to insight training should avoid lying down unnecessarily, except to sleep at the appropriate time. If you are tired and wish to rest for short periods, try to keep continuous mindfulness.

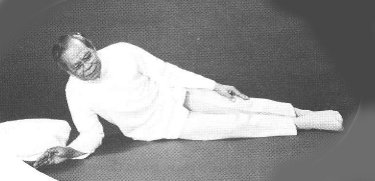

Take a position which will not induce sleep. In reclining the body, mindfully lower the body to the surface, noting contact. Slowly lift the legs, one at a time. Mindfully note "rising" and "falling" of abdominal movement, "lying" and "touching." Find a clear touching point.

As a beginner, if you do fall asleep, try to establish mindfulness the moment you awake. When awake, try to note the intention to rise; focus on each and every movement in connection with rising.

What are you doing? Reclining. What is reclining? Body (form) is reclining. What knows reclining? Mind knows reclining.

Rhythmic Practice — Hand-By Hand Mindfulness

We do not know where or when Vipassana meditation teachers developed the Rhythmic training in mindfulness. Perhaps this practice was devised over a hundred years ago and handed down from teacher to student. Up to the present time, a number of meditation masters in Thailand and Burma teach this technique to further cultivate moment to moment mindfulness. The increased number of movements gives mindfulness more "work," that is, additional opportunities arise for the momentary focusing on objects in their rising and falling stages.

The premise for this instruction is based on the Commentary to the "Four Foundations of Mindfulness" discourse (Maha Satipatlhana Sutta). It is a complementary practice to mindfulness focused on abdominal movement and the walking practice. As with the slow walking movement, this practice will soon become familiar. The beginner need not be concerned about forgetting any steps. Just focus "forgetting," and resume the sequence. Rhythmic practice is appropriate for both solitary and group practice. It can be used by the meditator who is fatigued or ill.

The speed of the movements varies with experience. Make a resolution to perform rhythmic practice for 10-15 minutes

Note intention to move right hand. Mindfully raise hand and note stopping. Bring hand to abdomen, but stop before touching; touch abdomen.

Mindfully raise left hand; stop. Bring to abdomen, but stop before touching. Touch abdomen. Bring EACH hand back to the knees, step by step.

Since all mental and physical objects are of equal value in mindfulness training, the meditator can incorporate the training very easily into mealtime periods. Take your time at meals and eat leisurely. It's part of your practice.

On entering the dining room, far example, look at and place the hand mindfully on the back of the chair. If using two hands, focus on one hand. Withdraw it slowly, and note moving. Focus awareness on bending and lowering the body and touching the surface of the chair.

Step by step mindfulness can be maintained if you follow the recommendations below. It's really quite easy.

MINDFULLY:

- Look at food, etc.

- Note if there is a feeling of hunger.

- Acknowledge intention to move the hand which is placed on the knee.

- Turn one hand until it rests on its edge.

- Raise it straight up.

- Lower the hand until it touches the utensil.

- Note touching the utensil. Acknowledge its hardness, etc.

- Grasp the utensil.

- Lift the utensil.

- Move utensil forward.

- Move utensil down to food.

- Spear, spoon or cut food, adapting as necessary. If you need the use of both hands, focus on only one hand.

- Lift the utensil and food.

- Bring to the lips; stop.

- Acknowledge touching the lips.

- Note opening the mouth.

- Place food in mouth.

- Close lips.

- Bring utensil back to table.

- Lower utensil.

- Stop before lowering utensil to table.

- Set utensil down and note letting go of fork, spoon, etc.

- Bring hand back to knee, lowering it mindfully.

- Chew food by focusing on the action of the jaw. You may close your eyes, if you wish. Note texture, heat, cold, etc. When tasting flavor, stop chewing and focus on taste. Swallow food.

- Focus on knowing that mouth is empty of food.

- Notice if there is a feeling of fullness in the stomach.

Repeat steps during the meal. Mealtime is a new experience. Many details regarding eating will gradually arise in consciousness.

Mindfulness during intensive practice is like an electric light turned on in the dark, sharply revealing every object. General mindfulness, however, is actually awareness mixed with delusion and is similar to our everyday mind. Like an electric light switched on in daylight, the brightness is diffused by the sun. So a beginner who only practices general awareness scatters mindfulness.

During training in an intensive course with other meditators, however, there are certain activities which, for practical reasons, cannot be greatly slowed down, such as during bathing. During such times, general mindfulness allows one to focus on the predominant object in consciousness, resuming step-by-step (object-by-object) mindfulness as soon as possible.

A meditator in training should avoid any complicated activity which is likely to cause loss of mindfulness. For this reason it is best to simplify activities as much as possible when entering an intensive period of training.

Concluding Intensive Practice — Transfer Of Merit Of Wholesome Deeds

The performing of meritorious deeds of body, speech and mind as wholesome endeavors (or karma) have a number of interpretive levels.

The practice of Vipassana meditation, which encapsulates the entire Noble Eightfold Path, is merit of the highest order. Dedicating the merit of one's practice to all sentient beings is an ancient tradition in Buddhism. It expresses the aspiration that other beings rejoice in deeds of merit. By rejoicing in another's good deeds and expressing sympathetic joy, one realizes a pure and unified mind.

In sharing merit, the meditator remembers one's teachers, parents, family, friends, indifferent persons, enemies, etc., extending the range of merit equally and impartially to all beings.

After concluding a period of intensive training, the meditator is released from the observance of the Eight Precepts. Buddhists may then observe the Five Precepts for laity.

The meditator may consult the teacher for guidelines in bringing the practice of insight meditation into daily life.

Correcting Meditation Problems

How To Handle Physical Pain In Training

When pain arises in any of the postures (occurring mostly in sitting), note it and return to the "anchor" object of abdominal breathing, for example. If it intensifies and you need to shift position, first acknowledge the intention to move, and slowly adjust the body, observing each and every movement and any emotional states which may arise in connection with sitting.

DO NOT use ego force to maintain any posture. Suffering, which happens by itself, forces the body to change. Sitting through pain (especially for the beginner) causes defilements to arise. Only the experienced Insight worker can sometimes separate the image of pain from hurt.

It is Wrong View that self can control pain. Some meditators force themselves to sit through pain in order to see more suffering, but that merely creates intentional pain which is artificially induced.

Please remember that Vipassana meditation is solely a mental training.

When mindfulness and concentration have sufficiently developed, certain new aspects of pain will emerge.

How To Correct Sleepiness And Dullness

Beginners will invariably experience sleepiness and dullness in early phases of practice. Note these mental states when they touch the mind.

To counteract these states, keep the eyes open, stands walk, or wash the face. Use skillful means to awaken the mind.

A dull, sinking mind occurs when an excess of CONCENTRATION appears in consciousness. MINDFULNESS is then too weak to observe the flux of mental objects. Sleepiness and dullness are an indication that the meditator has regressed to practicing concentration meditation.

It is important that the Inslght meditator understand that only MOMENTARY CONCENTRATION is needed for Vlpassana meditation.

How To Work With Severe Emotional Pain In Early Training

Mental suffering connected with past (or future) events occurs only in the present moment. It is the present moment, with its associated emotional states, which touches the mind, causing a shift in mental equilibrium. The origin and terminating points of stress, conflict and frustration actually have the same point of contact. The eradication of mental pain takes place when delusion is no longer present and mindfulness arises in consciousness.

If a new meditator suddenly experiences the rising of severe suffering, mindfulness may be too fragile to dominate such strong emotion. In fact, mindfulness may be entirely lost at that time.

To remedy the situation, a corrective switch to concentration techniques will help to weaken intense emotion, while still conserving a measure of mindfulness so that practice can continue. When the emotional state is made manageable, then the concentration technique is gradually released permitting mindfulness to once again return. By such self-correction, insight practice begins to strengthen and mature.

At this time, a meditation teacher's close and skillful supervision is invaluable.

Later, when mindfulness matures, the meditator will be able to focus on the rising-and-falling of strong emotion and "cut off" these states on a momentary basis.

How To Handle Recurring Memories And Overactive Imagination

The practice of Vipassana meditation is concerned only with the present moment of reality. The mental states detailing past events or projections into the future are simply noted as "remembering," "imagining" or "planning." They are not considered purer objects of mindfulness in that they are not present reality, such as seeing, hearing, etc.

When these mental states arise, note them and return to the "anchor" object of abdominal breathing or the movement of walking, etc. If the reappearance of memories or imagination persists and causes an excess loss of mindfulness, acknowledge "wandering mind."

If the novice meditator cannot observe these states arising-and-disappesring, then simply change the object, e.g., open the eyes, walk mindfully instead of sitting, etc.

Vivid memories or flights of the imagination are mental objects that are simply too potent for fragile mindfulness to observe with clarity. Only the well-developed mindfulness of an experienced Insight worker can release their persistent return.

Printable Version

Printable Version